Thinking back on the last couple

of

posts, a couple of questions arise naturally. First, there is the question

of the survival of regimes in general, not just democracy: if most democracies

die within 15 years or so, what is the median duration (the “half-life,” if you will: the time

it takes for half of them to be gone) of other regimes? And second, there is

the question of the relationship between the half-life of regimes and the

half-life of leaders: do regimes whose leaders tend to have longer half-lives also

have longer half-lives? My interest in these questions stems from my current

research on the question of legitimacy: my sense is that legitimacy matters

much less than people usually think to the survival of large-scale patterns of

political power and authority, so I’m interested in trying to figure out if

there are systematic differences in survival between more and less “legitimate”

regimes and other political structures. So this is another exploratory post,

with lots of graphs.

How do we measure the duration of non-democratic

regimes relative to democratic regimes? Though democratic regimes are not

always straightforward to identify, non-democratic regimes come in a much wider

variety of forms – from hereditary, absolute monarchies to single party regimes

and multiparty hybrids, and some of these forms shade gradually into one

another over the course of many years. (For a sense of this variety, consider

the differences between Mexico before the 1990s under the PRI, whose presidents

succeeded each other with clockwork regularity every six years and a lively opposition

existed but could never win the presidency, North Korea today, where opposition

is non-existent and succession is controlled by a tiny clique, and Mubarak’s

Egypt.) To get a handle on this question, I’m going to use the Polity IV dataset,

which codes “authority characteristics” in all independent countries (with

population greater than 500,000 people) from 1800 to 2010. (I’ve been convinced

by Jay Ulfelder’s work that the

DD dataset I used in

my earlier post is not appropriate to study comparative regime survival due

to the way it codes certain democracies where alternation in power has not

occurred as dictatorships, which systematically biases the survival estimates

of democracies upwards).

The Polity dataset is fairly rich. Most researchers

seem to use only the composite indexes of democracy and dictatorship it offers,

but these indexes, while useful, do not have a strong theoretical motivation,

as Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland argue

here. For my purposes, it is best to use the dataset to extract those authority

characteristics of political regimes it purports to measure: the mechanisms of

executive recruitment, the type of political competition, and the degree of

executive constraint. Mechanisms of

executive recruitment include hereditary selection, hybrid forms combining

hereditary and electoral mechanisms, selection by small elites, rigged elections,

irregular forms of seizing power, and competitive elections; types of political

competition range from the repressed (all opposition banned, as in North Korea)

to the open (typical of thriving democracies); and executive constraints range

from unlimited to “parity” with the legislature. (See the Polity IV codebook

for a full discussion). In theory, the dataset distinguishes eight kinds of

executive recruitment mechanisms, ten types of political competition, and seven degrees of executive constraint, plus three

different kinds of “interruption” (including breakdowns of state authority,

loss of independence, and foreign invasion and occupation), leading to a

possible 563 possible patterns of political authority, but these dimensions are

all highly correlated (over .99); indeed, only 212 combinations of executive

recruitment, political competition, and executive constraint actually appear in

the date, most of them only once and for short periods of time, and it is

obvious that some combinations do not even make sense. (And those that do make

sense do not always capture all the information we would normally want about a

political regime: Polity has no good measure for the extent of suffrage in

competitive regimes, for example). But the dataset helpfully indicates how long

each of these patterns last, so we can attempt a first cut at the question of

the half life of regimes using a Kaplan-Meier graph:

The half-life of an “authority pattern” – a combination

of an executive recruitment mechanism, a type of political competition, and a

specific form of executive constraint – is 6.6 years, though the tail of the

distribution is very long: some of them have lasted for upwards of a century. Switzerland,

for example, has had the same authority pattern for 162 years, and Afghanistan

retained the same authority pattern from 1800 to 1935 (a hereditary monarchy). As

it happens, social and political life comes to be mostly structured in most

places by the long-lasting patterns, but most

patterns of authority do not last that long. Incidentally, at this level of

abstraction there are no great regional differences in the half-lives of

authority patterns, though it does seem as if authority patterns last slightly longer

in Europe and the Americas than in Africa and Asia:

Yet an “authority pattern” is too amorphous

a unit of analysis. We might get a better handle on the question of comparative

regime survival by looking specifically at the mechanism of executive selection,

since the manner in which the chief power in the state is selected is normally

thought to be quite important and to have far-reaching consequences: whether

supreme power is achievable by hereditary succession only or through designation

within a closed elite or via competitive elections or some other means seems to

have important consequences.

Of all the mechanisms of executive selection

identified in the Polity IV dataset, only one, “Competitive Elections,” is

unambiguously democratic by most people’s lights. Though within the dataset the

fact that a regime has competitive elections is no guarantee that it will also

have universal suffrage, for the most part “competitive elections” identifies most

countries that most people think are democratic. We can thus calculate the

duration of all periods of “competitive elections” and compare them to the

duration of all “non-democratic” periods – those periods where executive selection

happened through some other means. The details are somewhat tricky (see the

code), but here are the results:

Some notes. As we might have expected from

the discussion in the

previous post, full hereditary monarchies (Russia under the Tsars, Saudi

Arabia, Iran under the Shah, Portugal and Romania in the 19th

century, Nepal in the 19th century, among others; there are 65

episodes in 40 countries in the dataset) have the longest half-lives (nearly 32

years; this increases if we collapse the two hereditary monarchy categories.

Note these are not “constitutional” monarchies like the British one). But competitive

electoral regimes are no slouches, with a half-life of about 17 years (in

keeping with Jay’s numbers in

this post, though he uses a different dataset), and as time goes on their

survival rates seem to converge with those of monarchies. Similarly, “limited

elite selection regimes” (e.g., single party-communist regimes, where a narrow

clique selects the leader without open competition) have a half-life comparable

to that of democracies, but as time goes on they tend to break down more; their

survival rates seem to diverge from those of competitive electoral and

monarchical regimes. Low survival rates are found especially among political

forms that appear to have internal tensions, such as competitive

authoritarian regimes, where elections exist and are contested by an

opposition, but it is very hard for the opposition to attain real power (e.g.,

Zimbabwe today). I confess I don’t really understand Polity’s “Executive-guided

transition” category, but it’s obviously a regime that is turning into

something else (the Pinochet regime in Chile after the 1980 referendum but before the return of competitive elections counts, for example), and “ascription

plus election” includes regimes where the monarch retains some real power but

the legislature and other executive offices are no longer under its thumb (only a few are recorded in the data,

including Belgium in the late 19th century and Nepal in the 1980s

and 90s); it makes sense that such regimes, halfway between “real” monarchies

and purely constitutional monarchies like the British, should have short

half-lives as the conflict plays out and either turn into competitive electoral

regimes or into more absolute monarchies.

It is also interesting to compare the

relative survival rates of competitive electoral patterns of authority vis a vis periods where selection

happens by non-competitive electoral means (regardless of whether the selection means stay the same):

Though the difference seems to narrow as

time passes, the half-life of non-democracy since the 19th century

has been a bit longer than the half-life of competitive electoral regimes (23

vs. 17 years). In sum, political regimes do not last much more than a

generation.

(For those still following, the regional

breakdown indicates that competitive electoral periods have had the longest

half-lives in Europe and the Americas, whereas non-democracy has had the

longest half-lives in Africa and Asia; no special surprises there, though I am not sure about the reason).

How does this relate to the half-life of

leaders? For that, we turn to the ARCHIGOS dataset by Goemans,

Gleditsch, and Chiozza, which contains information about the entry and exit

date of almost all political leaders of independent countries in the period 1840-2010.

It’s a fantastic resource – more than 3000 leader episodes, and information on

their manner of exit and entry. And the conclusion one must draw from examining

it is that power is extremely hard to

hold on to; a ruler’s hold on power seems to decay in an exponential manner

(note I haven’t checked that the decay really is exponential in the technical

sense, though I'm thinking of doing that). Over this vast span of time, covering all kinds of political regimes, the

half-life of leaders is only about 2 years, or a third of the median authority

pattern, as we might have expected from the previous post (though the half-life

of leaders is even smaller here):

Yet of course it is the people who beat the

odds – those who last much longer than the average leader – the ones who shape

social and political life. (There’s an endless parade of mediocrities in the dataset, two-bit prime ministers gone after a few months of ineffectual dabbling and the like).

(But don’t some leaders come back to power

after losing it? In fact, the vast majority of leaders only attain power once, and never return

to power, though about 100 did manage the feat three or more times. In fact,

practice does not help; survival in power only appears to decrease the more previous times the leader had been in power,

though note that the uncertainty of the estimates also increases, and one might

expect that age would take its toll too).

We are now in a position to extend the analysis in the post below by merging the Archigos and the Polity

dataset to calculate the survival curves for leaders conditional on the pattern

of executive recruitment. Though I would take these curves with a grain of salt,

here are the results:

As expected from the previous post, it’s good to be king

– the half-life of absolute kings is about 12 years (and it’s almost always

king: there are only 41 female leaders in a 3000 case dataset). Interestingly, a

similar result for the half-lives of Chinese emperors is reported

here (10 years: Khmaladze, Brownrigg, and Haywood 2010, ungated)

as well as for the

half-lives of Roman emperors (11 years: Khmaladze, Brownrigg, and Haywood 2007, ungated).

There is something about the deep structure of monarchies in many different

periods and societies, it seems, that points to a half-life in power of about 10-13 years

for monarchs.

More generally, authoritarianism pays in terms

of leader tenure, despite the fact that non-competitive regimes do not always last longer than competitive ones. The highest

half-lives of leaders beyond monarchs are found in limited elite selection

regimes, executive-guided transitions (where non-democratic leaders are

changing the rules), and competitive authoritarian regimes; but democracies are

more lasting than most of these regimes (except for monarchies; see above).

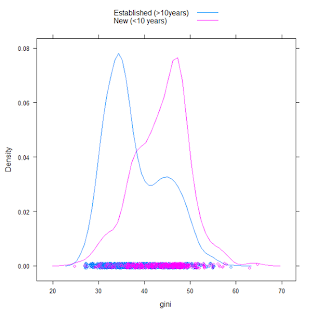

Another way of looking at this is to calculate what we

might call the “personalization quotient” of a regime: divide the half-life of

the leader (for a given regime) by the half-life of the regime to get an idea

of the percentage of the regime half-life that a leader is expected to last. So

a monarch is expected to last about 37% of the half-life his regime (31.86 /

12); this is the most intensely personalized of regimes, as one might have

expected given that it is devoted to the maintenance of a family line. The

next most personalized regimes are competitive authoritarian regimes (28%), “self-selection”

regimes (15%), limited elite selection regimes (16%), and “executive-guided

transitions” (40%; this is pretty much by definition, however, so I don't make much of them). A competitive

electoral regime has a personalization quotient of 8% - an expected leader half-life of about 2, divided by an expected regime duration of about 17 years. From the point of view

of such a leader, it pays to try to move towards a competitive authoritarian

regime, and it pays for the leader of a limited elite selection regime to move

towards a formal hereditary monarchy (as is happening, in a sense, in North

Korea right now, and almost happened in Egypt and Libya).

But are authoritarian regimes more risky, so that leaders will try to hang on to power more? We can also look at that using the archigos dataset. Though leaders in non-democratic regimes have a slightly higher risk of leaving office with their heads on pitchforks or hanging from lampposts, the vast majority leave by "regular" procedures.

More, perhaps, could be said. I’ve been wondering, for

example, about whether there is a relationship between the breakdown of

particular regimes and the tenure of leaders, though I’m not sure how to go

about tackling that question. From the point of view

of the study of legitimacy, however, what strikes me is the general fragility

of patterns of authority and rule: few patterns of authority are expected have

half-lives that exceed a single generation, and most don’t last nearly as long,

regardless of their “legitimation formula” – heredity, competitive elections,

ideology, whatever. Of course, some beat the odds, especially some competitive

regimes and some monarchies, and these shape history. But the historical

evidence suggests that they are in a sense the exception rather than the rule.

Code necessary for replicating the graphs in this post,

plus further ideas for analysis, here and here. You will need to download the Polity IV and ARCHIGOS datasets

directly, and this file of codes from my repository.

[Update: fixed some typos, 9 Feb 2012]

[Update: fixed some typos, 9 Feb 2012]