(Continues the discussion in this post, with more graphs, more data, more theory, and more verbiage. Mostly exploratory, considering further research. Statistician General’s warning: all statistical analyses in this post should be taken with large heapings of salt, since they have not been produced by a trained and licensed statistician and do not provide appropriate guidance regarding the uncertainty of any estimates. If you don’t mind a spot of quantitative social science from someone who was not trained in these dark arts but who is overly excited about learning to produce pretty graphs, go on.).

In an earlier post, I discussed some recent models of the relationship between inequality, political regime types, and democratization (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson or Boix). The basic ideas in these models are pretty simple, even simplistic. In democracies, governments are (ideally, at least) responsive to the interests of the majority of the population, and in particular to the interests of the “median” voter (the voter in the middle of the distribution of income among voters), whereas in dictatorships governments are more responsive to the interests of smaller – sometimes much smaller – groups. To the extent that dictators are responsive to the interests of constituencies where the median income is higher than the median income in society (the typical case), we should expect that dictatorships will tend to redistribute less (to lower income groups) and have higher levels of income inequality than democracies, other things being equal (and other things are not always equal!). Moreover, these models indicate, the higher the level of inequality, the higher the degree of social conflict over the level of redistribution and ultimately over the type of regime, since “one off” redistribution in the face of occasional protest or other contentious action is not sufficiently “credible.” Hence we should expect that in the long run, democracy should be unsustainable at very high levels of inequality, and the only stable regime outcomes should be forms of dictatorship: “leftist” dictatorships where the poor (or rather, people claiming to act in their name) expropriate the rich, and “rightist” dictatorships where richer elites restrain redistributive demands by non-elites through coercive means. Finally, we should observe more regime change at higher rather than lower levels of inequality, more stable regimes at lower rather than higher levels of inequality, and more transitions to stable democracy at middle levels of inequality.

Using data on inequality from the University of Texas Inequality Project (1960-1996) plus data from the World Bank (which I didn’t use in my previous post but extends the UTIP data to 2008 for some countries), and data on political regimes by Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland (1956-2008), we can see that some of these theoretical expectations appear to be reasonably well validated.[1] Here is a plot of the distribution of inequality, as measured by the gini index, in democracies and dictatorships (reproducing the first plot in my earlier post, but with World Bank inequality data added):

The median gini for democracies is 38.6; the median gini for dictatorships is 45.6. (means 40.1 and 44, respectively, with N= 3,321 observations between 1963 to 2008; similar patterns appear if we look only at particular periods, like the post cold war era). If we could add the vast majority of non-democratic systems in human history, the pattern would be even more obvious; as Lindert, Milanovic, and Williamson have argued, ancient non-democratic societies (i.e., the vast majority of all ancient agricultural societies) were at the “inequality possibility frontier” – elites extracted the maximum surplus from society.

But as I mentioned in my earlier post, it is obvious that the distribution of inequality in both democracies and dictatorships is very wide: lots of democracies have high gini values, and lots of dictatorships have low gini values. We do not see two clearly defined “peaks” in the distribution; rather, the distribution of inequality in both democracies and dictatorships appears to be “bimodal” – with distinct high inequality and low inequality peaks.

This is relatively easy to explain in the case of dictatorships: most of the dictatorships with low inequality appear to be communist countries, though there are fewer of these – exactly what we would expect from the theoretical models. (It is, after all, easier to organize a coup than a social revolution). Here’s a picture of the distribution of inequality in dictatorships only, split among communist and non-communist dictatorships:

The communist dictatorships are clustered narrowly at a low level of measured inequality (median gini 28.9; more on the “measured” bit in a minute), while the non-communist dictatorships have a somewhat broader distribution centered around a larger level of inequality (median gini 45.9).

The bimodal distribution of inequality in democracies is harder to explain; like dictatorships, democracies appear to have both a low inequality and a high inequality equilibrium. Why?

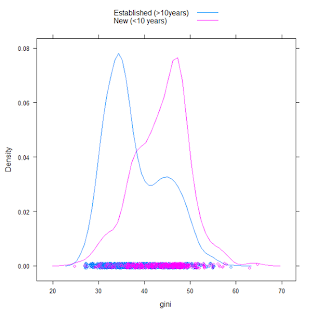

One factor that might seem to matter is simply the length of time a democratic regime has been in existence: redistribution capable of affecting the level of inequality in a society seems to take time. Here’s a plot of the distribution of inequality in democracies, split between those democracies that have endured for less than 10 years and those democracies that have endured for more than 10 years:

Younger democracies appear to have larger levels of inequality (median gini for established democracies: 36.2; median gini for new democracies: 44.4). In fact, while democracies appear to become more equal with time, dictatorships appear to become less equal:

And while it seems that democracies become more equal as they become richer, dictatorships appear to remain as unequal as before:

Moreover, it is obvious that democracies do become quite unequal sometimes. The USA is an obvious case. Here it is interesting to note that the USA is not a new democracy and is clearly quite rich, so (given the previous graphs) we would predict inequality to go down, but it seems to have been on an upward trend even looking at the long run (not just at the last decade):

(Similar patterns are visible in many rich democracies – France, for example). More on why this might be the case in a minute. But let’s think of different possibilities for why democracies might (or might not) decrease inequality. Consider what happened in Poland after the collapse of communism (similar trends are visible in Hungary, Bulgaria, and other communist countries that transitioned to democracy):

In this case, it seems that the transition to communism triggered the wholesale conversion of political access (the main inequality in these societies) into monetary assets, leading to a higher equilibrium level of measured income inequality. Measured income inequality was actually misleading about the distribution of power in communist countries; just because they were “equal” societies in income terms did not mean they were “equal” societies in the things that income can buy elsewhere, and when the basis of the regime changed, the “true” inequality in society reasserted itself in income terms, though it still remained relatively low in comparative terms. (An alternative story: perhaps with the to a market economy, people in Poland and other communist countries had the opportunity to trade off more income against increased inequality, and they took it. This is also plausible, but not my focus here; it is less plausible in places where wholesale conversion of communist apparatchiks to well-connected biznesmeni took place, as in Russia).

Sometimes democracy is, in a sense, too successful at an earlier time in redistributing income, prompting a reaction from elites. Consider Chile:

Inequality decreases fast until the 1973 coup, partly because of redistributive policies pushed by the left, at which point it increases again greatly. The interpretation is obvious: the elite could not stomach so much redistribution, and returns Chile to a higher level of inequality by coercive means. (The military Junta led by Pinochet made this point rather explicitly: their mission was to destroy communism and its leftist sympathizers in Chile. So they arrested and sometimes killed the leaders of leftist parties and coercively defanged or banned labor unions). After the transition to democracy in the late 1980s, inequality seems to stabilize at a higher level: the new democratic governments are constrained in the amount of redistribution they can undertake, both constitutionally and prudentially, and at any rate, the structure of Chilean society changes – labour unions have less power, elite assets are more mobile, etc. So elites are willing to transition to democracy, without fearing Allende-style redistribution. It’s like Chile’s long-term “natural” rate of inequality – the rate that is consistent with the maintenance of a democratic regime is somewhere around a gini of 45.

South Korea presents yet another possibility:

This pattern is also nicely consistent with the basic theory, though in a different way. Here we have a right-wing dictatorship facing a communist neighbour that presented a credible but far more redistributive model. (After the Korean War and until the mid 70s, most people thought the North was doing better than the South). In these circumstances, democracy was too threatening to elites: it was too easy to imagine a communist takeover by electoral means. It was still necessary to defuse the threat of social revolution through some redistributive measures (there were some fairly extensive land reforms, if I am remembering correctly), but not through institutionalized democracy, which was too risky. Promises of redistribution were made credible by the communist threat to the north, and in fact carried out to some extent. Eventually, however, inequality decreased sufficiently and the Northern model became sufficiently unattractive that democracy became much less costly to elites, leading to a transition in the late 1980s. Inequality again appears to stabilize after the transition.

A fourth pattern is found in Thailand:

(The highlighted points are years of successful coups; there were more unsuccessful ones, and the 2006 coup is not shown – no gini data for that year). We might interpret this as follows. Democracy is introduced in the late seventies (though resisted, as shown by coups in 1976) and is immediately associated with a decline in inequality, presumably through redistributive policies, but remains plagued with coups (more unsuccessful ones not shown), mostly supported by the elite. Yet the elites do not have enough power to sustain a military regime indefinitely; military coups merely postpone the resumption of redistributive politics. (I don’t know of Thailand inequality data for 2006 and after, but it would be interested to see what it looks like).

The individual patterns are not always so clear. In fact, in most cases where there is data, no pattern is readily discernible: the aggregate pattern is clear, but the level of inequality in individual countries sometimes appears to fluctuate without any apparent connection to regime type. In some countries, transitions to democracy occur as inequality is going down (the South Korean pattern), in others, as it is going up; and in others the trend appears flat, at least given the available data. In some cases, periods of dictatorship are associated with increases in inequality, in others with decreases in inequality, and similarly for periods of democracy.

I suppose someone with knowledge of individual country histories could make sense of any given country pattern, and someone with better statistical skills could design an appropriate measure of whether inequality goes up or down, on average, during democratic or dictatorial periods. My best guess is that you would need to do a fixed effects model – controlling both for factors that affect the level of inequality at a global scale, and for country-specific factors that affect the level of inequality in a specific country. For example, inequality appears to have increased in many countries in the world in the last decade, presumably due to changes in the global economy – but more in some countries than others, presumably due to particularities of each country, including the influence of the political regime. So we would need to distinguish those global effects that are not subject to political control from the effects of political regime on inequality. Fiddling around a bit with something along these lines (using some advice provided by Eric Crampton, though all errors are mine), I cannot find any specific pattern when controlling for obvious things; if anything, democracy seems to increase inequality over time relative to dictatorship when using a full time series model (though it may be that I am not very good at interpreting the coefficients I’m getting, or that I’m mispecifying the thing somehow; for example, maybe one needs specific kinds of lags, etc. If you have expertise and would like to collaborate on figuring this out, please let me know.).

But what does come out of that fiddling as an important factor determining the level of inequality over time is the number of previous transitions to authoritarianism, which we might interpret as a proxy for the power of the elite to prevent redistribution. In various simple regressions, an additional transition to authoritarianism seems to increase the level of inequality by a unit in the gini index, and democracies with higher numbers of transitions to authoritarianism in the past seem to exhibit higher long-term levels of inequality. Consider this scatterplot:

When looking at the average gini of democracies that have existed for more than ten years, we see that democracies with fewer transitions to authoritarianism in the 58 year span (1962-2008) of the dataset seem to be scattered all over the place, though the upper range is less populated. But inequality clearly increases with previous transitions to authoritarianism, and the range of “permissible” inequality seems to narrow – with more transitions to authoritarianism, the narrow the range of inequality and the higher the mean. (The pattern is visible when looking not just at the mean gini of democracies existing for more than 10 years, but also at the mean gini of all democracies).

How can we understand this? Here’s one possibility, and (finally) the justification for the title of this post. With fewer experiences of dictatorship in the recent past, democracies can enact a wide range of redistributive policies, depending on beliefs about luck and hard work, “ideological investment” by various interested parties, reasonable arguments, the organizational ability of various actors like labor unions and business associations, the visibility of wealth and the economic structure of society, etc. Such policies have a wide range of consequences, and so inequality may fluctuate quite drastically over time in established democracies, though it will in general experience some downward pressure relative to dictatorships. Perhaps there are “arms races” in which organizational and ideological innovations by representatives of the “left” (labor unions and particular forms of contentious politics like strikes, Marxism, etc.) are in time neutralized by organizational innovations by representatives of the “right” (think-tanks and particular business organizations, legal ways of constraining the power of unions, “neoliberal” ideas, etc.) and vice-versa, so that in the long run, inequality follows a trend determined by structural factors in the economy: the long-run “natural rate of inequality” for the society, kind of like what economists sometimes refer to as the “natural rate of unemployment.” Something like this has perhaps happened in the USA (at least if we credit people like Hacker and Pierson), where “right-wing” actors developed organizational and ideological innovations to counter the organizational and ideological tools of the “left;” but in the long run, what we should see, short of a change in regime, is a reversion to the mean trend, itself determined by economic factors that are not easily susceptible of political control.

In some societies, however, some of these redistributive policies prove intolerable to elites, who then stage coups. When the society returns to democratic rule, representatives of non-elites know something about the ability of elites to credibly commit to extreme measures in the face of redistributive policies, so the range of distributive outcomes that appears acceptable to all narrows. (Something like this appears to have happened in Chile, for example, where successive “left” governments have “learned” from the past not to engage in certain kinds of redistributive policies). The more successful coups there are in a society, the narrower this range. Over time, you see the development of a bimodal distribution of inequality in democracies: societies where people have learned about the “red lines” that ought not to be crossed have a higher long-run level of inequality given the structure of their economy.

As noted earlier, take all of this analysis with a grain of salt; this is more exploratory than anything else, and I am certainly not a properly trained statistician. I am just curious, and considering further research on these topics. (Collaboration possibilities are also welcome).

[1] Data on inequality is patchy and often of poor quality. The UTIP dataset is basically the best there is for cross country comparisons over time (going back as far as 1963 for some countries); the World Bank adds some more data points, especially after 1996 (when the UTIP data ends). I mentioned in a previous post why I like the Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland dataset on political regimes so much - in particular, it operationalizes a clear and theoretically justified distinction between democracies and non-democracies - but more perhaps later.