(6,500 words on Daniel Leese’s fascinating book Mao

Cult: Rhetoric and Ritual in China's Cultural Revolution [Cambridge

University Press, 2011], by someone who is no expert on Chinese

history, but has lots of non-peer-reviewed theories about cults of

personality. Thanks to Andrew Ivory for the book recommendation, and to my colleague Jason Young for conversation on the topic and help with the Chinese characters.)

Longtime readers of this blog know I am fascinated by the

phenomenon of cults of personality. (Click here

for some of my previous posts on the subject). In fact, I’m working on a paper

on the subject and gathering data on the prevalence of cults and cult-like

phenomena in the 20th century, so I was of course delighted to hear

about this book. It did not disappoint: Leese’s book is everything a scholarly

monograph should be. It is deeply learned, thoroughly researched, and well

written; and the story it tells is fascinating. Not the least of its merits,

from my perspective, is that it provides supporting evidence for some of my

own pet

ideas about

cults of personality, though it also has led me to rethink and nuance others.

The idea of a “cult of personality” is in some ways a

peculiarly modern one. Practices of “leader worship” were of course not unknown

in the past; one might almost say that they were basically the default way in which peoples related to leaders

in “pre-modern” state societies, from the recognition of Egyptian Pharaohs as

god-kings to emperor worship in China, and from the cults of Hellenistic

monarchs and Roman emperors to the sacralisation of monarchs in Medieval Europe.

But such cults could only become a theoretical and political problem in the

context of societies which claimed to be socially or politically egalitarian,

as most

societies do today; it is only against a background expectation of relative

equality that the practice of leader worship appears as an aberration, in need

of special justification or explanation. And this problem was especially acute

in communist societies, where even formal terms of address had been consciously

engineered to express the idea of equality (“comrade”), yet nevertheless appeared

to be embarrassingly plagued by forms of leader worship.

It is thus no accident that the term itself (“cult of

personality”) came into wide circulation at around the time of Khrushchev’s

“Secret Speech” of 1956, which condemned Stalin’s “cult of the individual.”

The pattern is unmistakable; we can see it, for example, in the books indexed

by Google in a variety of languages. So, for example, in English:

|

| Figure 1: Frequency of "Cult of Personality" and related terms in the English corpus of books in Google |

Or, more emphatically, in Russian:

|

| Figure 2: Frequency of "Cult of Personality" and related terms in the Russian corpus of books in Google |

In Chinese the pattern is somewhat more muddled (there are

some weird artifacts if we look at mentions of the term before 1940), perhaps

because the Google corpus is less reliable for Chinese texts, and perhaps

because of the

simplification of the Chinese script that was happening around the 1950s

makes it difficult for us to capture all the mentions of “cult of personality”

in books

published before and around the mid-20th century. Yet the basic

shape of the usage curve is still there, showing the impact of Khrushchev’s

speech, though it decays faster and rebounds more than in English or Russian,

for reasons that are not immediately clear:

|

| Figure 3: Frequency of "Cult of Personality" in the simplified Chinese corpus of books in Google |

Leese’s book takes the Chinese response to Khrushchev’s speech

as the starting point for its story. The speech could not but be seen by

Chinese leaders as a poke in the eye, especially Mao’s, whose cult bore some

resemblance to Stalin’s, even if it had diminished in intensity in 1956

relative to the late 40s. (In fact, the Chinese Communist Party had generally

prevented excessive open flattery of Mao during the early years of the People’s

Republic, with his consent; later “excesses” lay in the future). And by forcing

them to respond and to justify or change their practices, the speech also

threatened to produce shifts in power within the CCP. Nevertheless, as we shall

see, the speech ended up providing an unexpected impetus to the further

development of the Mao cult.

Leese argues that the cult first emerged during the later

years of the Chinese civil war as a mobilizing

device. It was consciously promoted by the top leadership of the CCP (not just

Mao) in reaction to the growing cult of Chiang Kai-shek on the Guomindang side,

and seen even by people who had doubts about overly personalizing Marxism as a

way to unify the party against their enemies. From this point of view, the cult

appeared as a form of what Leese calls “branding” (not my preferred term); and

it was specifically nurtured within the party through the practice of “group

study” of party history, which presented a mythical narrative of the Long March

under Mao’s “correct” leadership. At this stage the cult thus served both to

marginalize certain factions (e.g., the group of Soviet-trained cadres around Wang Ming, who had Stalin’s

favour) and to motivate party and army members in the continuing struggle with

KMT forces; to the extent that the cult also mobilized non-party members, it

would have done so mainly through general propaganda campaigns, an arena where

it had to compete with similar publicity by the KMT, at least in contested “white”

areas. With the victory of the CCP these mobilizing and unifying functions of

the cult became less important, though the party of course continued to control

the public display of Mao’s image, and the cult could still be used as one of

the instruments of centralization employed by the CCP (e.g., against Gao Gang in 1953-54, who developed

his own regional cult in China’s north-east and was eventually purged).

This is not to say that there was no demand “from below” for

cult practices. Since the CCP was in part a huge hierarchical patronage machine

with few formal mechanisms for promotion, signalling loyalty through praise –

sending congratulatory telegrams to Mao, for example, even when these were

discouraged by the CCP leadership – was a useful means of career maintenance

and even advancement. (You want to be the one local committee that does not send congratulatory telegrams? How

is that going to look?). But praise of the top leaders was tempered both by the

fact that it was embedded in a larger discourse where Stalin, not Mao, was the

pre-eminent leader of the communist world, and by the fact that the top

leadership of the party seems to have consciously discouraged extreme praise,

perhaps because it feared (not unreasonably, as it turns out) concentrating

power in Mao’s hands. The cult thus appears here not only as a mobilization device pushed from the top,

but as the unintended consequence of loyalty signalling by lower levels of the party, which tended to keep the

overall level of flattery relatively high, and inflationary pressures steady;

and it was clearly fuelled, though not fully explained, by the undoubtedly high

popularity of the party and the prestige of Mao as its leader during the early

1950s.

The death of Stalin, Khrushchev’s speech, and other

political developments disrupted this initial equilibrium, in which the expression

of loyalty to Mao had not yet crowded out all other signals of loyalty to the

party and the revolution, and had not yet colonized public space to the extent

to which it did during the Cultural Revolution. For one thing, the death of

Stalin had the effect of displacing

foreign leaders from their pre-eminent position in public displays, leaving Mao

to monopolize an ever larger and more central share of public space. Leese’s

book describes for example the faintly comical difficulties experienced by local

cadres when trying to organize parades and other festivities after 1953; the

question of whose portraits and what slogans to display, and in what order, was

evidently of great importance to them (a faux

pas could be harmful to one’s career prospects, I suppose), and yet

directives from the Centre became ever more confusing. Indeed, a directive of

April 1956 essentially declared that no guidance would be provided to local

party committees regarding whose portraits to display and in what order during

public events. Eventually the confusion seems to have been resolved in the

obvious way: portraits of foreign leaders were no longer handed out to marching

crowds at official events.

The effects of Khrushchev’s speech on the cult were at first

more negative. On the one hand, the CCP’s initial response to it fed into a

process of liberalization of the public sphere which had begun somewhat

earlier. (Leese interprets the directive relaxing control over the display of

symbols and portraits as part of this process). Criticism of the cult and other

forms of “dogmatism” was aired in high places, and support for collective

leadership expressed. At any rate, the party was (with good reason) confident

in its popularity at this time, and prepared to relax its control over the

public sphere. Leese thus takes the “Hundred

Flowers” campaign of 1957 to be a (botched) attempt at genuine

liberalization, though Mao himself later described it as a trap, a way to “lure

snakes out of their holes.” As time went on, however, both Mao and groups

within the party came to think that liberalization had gone too far: cadres

became demoralized and confused (which contradictions were good and which were

bad? Why had so many bad things happened since Khrushchev denounced Stalin?),

critics started attacking the party and even Mao directly, and Mao’s prestige

suffered:

The failure of the rectification

campaign [the “Hundred Flowers” campaign] led to a self-generated crisis of

faith in ... the CCP’s governance, and the responsibility was clearly to be

placed on Mao. He thus faced two “credibility gaps”: The campaign had tarnished

his image as omniscient helmsman of the Chinese Revolution among party members,

and the campaign’s indecisive enactment led non-party members to question his

authority over the CCP (p.

63).

(More worrying, perhaps, was the fact that the failed

rectification campaign had opened the doors to criticism of Mao by senior party

figures like Peng Zhen and

Liu Shaoqi, though Leese

does not make much of this.) At any rate, the problems with the rectification

campaign prompted Mao to take greater control over the propaganda apparatus and

to sharpen the distinction between “good” and “bad” criticism in a way that

left Mao more or less in control of determining which views fell into which

category. By early 1958, at the beginning of the Great Leap Forward, Mao had

even formulated a distinction between a “correct” cult of personality

(indicated by the term geren chongbai

个人 崇拜) and an “incorrect” cult (indicated eventually by the

term geren mixin 个人 迷信). The distinction sidestepped the theoretical problem

raised by Khrushchev’s criticism of cults by redefining “good” cults as a

worship of “truth,” but it was transparently driven by Mao’s understanding of

the cult “as an extrabureaucratic source of power that did not rely on its

recognition within the party elite” (p.

69). In other words, if there had to be a cult, Mao indicated that it

better be his as the representative of “truth,” or at least of those people he

could approve of, regardless of party views. As Mao said, quoting Lenin, “it is

better for me to be a dictator than it is for you.” (Much later, Mao told Edgar

Snow that Khrushchev’s failure to develop a cult had led to his eventual purge

by Politburo members, which shows that he thought of the cult as a useful

device to prevent challenges to his position from within the party). Moreover,

the cult seemed to Mao a good instrument for promoting a “lively, emotional

climate” that would motivate people to take a “great leap forward” toward communism,

just as the cult had served to motivate party members and soldiers during their

struggles against the KMT.

The articulation of the distinction between a “correct” and

an “incorrect” cult, however, opened the door to flattery hyper-inflation. As

Leese notes elsewhere:

... with the validation of a

correct cult it was not necessary any more to ‘praise the king the whole time,

but, so to say, without explicit praises’, as Paul Pellisson, court historian

of Louis XIV, once wrote. During the early years of the PRC, praise of Mao

Zedong in public discourse had by and large been curbed with Mao’s consent. But

after March 1958, references to the Party Chairman and his thought witnessed a

huge upsurge in the media, although in comparative perspective the excesses

were dwarfed by the Cultural Revolutionary rhetoric.

Cadres wishing to prove their loyalty could now stop

worrying too much about the question raised by Khrushchev of whether cults of

personality were compatible with Marxism-Leninism, and hyperbolic praise of Mao

and his latest “line” soon became a necessary instrument of career maintenance

and advancement within the CCP, though at the beginning such praise was still

carefully defined as praise of the “truth” (which just happened to be embodied

in the person of Mao and his works).

The praise soon came into conflict with reality, however. The

burst of flattery encouraged by Mao led to a flood of “completely

fictive numbers of both agricultural statistics and cultural artifacts in order

to signal adherence of the provincial cadres to the Party Centre” (p.

73). But the great famine of 1958-59 could not be hidden by mere

propaganda; for those affected by the catastrophe, the evidence of the senses

was of course in direct contradiction with the claims of Mao and his flatterers,

which challenged Mao’s prestige and credibility and offered opportunities to

disaffected people within the party. This challenge was the most serious yet to

Mao’s position, in part because the famine fomented dissatisfaction within the

People’s Liberation Army, whose soldiers could not be fully isolated from

reports coming in from family members about the situation in the countryside.

(Not even the Central Bureau of Guards, the unit in charge of guarding the

leaders of the party, was immune to unrest). Soldiers were asking: is “Chairman

Mao ... going to allow us to starve to death”? (quoted in p.

96). Even more seriously, Marshal

Peng Dehuai, who had enormous prestige within the PLA, became severely

critical of Mao’s policies. This was an intolerable challenge to Mao’s

position, who feared a coup; and though Peng was eventually purged (with dire

consequences for the Chinese population, since Peng’s public criticism led Mao

to stubbornly stick to policies that the party had been quietly about to

correct, according to Leese), the need to regain control over the army was

pressing. Lin Biao (the

youngest PLA Marshal) proved the man for the job.

For one thing, Lin was not shy about praising Mao, and knew

how to wield the charge of insufficient adherence to Mao Zedong thought against

his enemies within the party and the military. In fact, he was able to shift the norms prevailing at the top of the

CCP so that “adherence to Mao Zedong thought” became the sole criterion of loyalty. In practice, this meant that any

statements critical of Mao – uttered at any time in the past – could be used as

incriminating evidence of disloyalty, and used in factional disputes which

nearly destroyed the party, and served to purge many people at the top.

There is a puzzle here, however: as Leese puts it, “[i]t

seems difficult to explain why Liu Shaoqi and other CCP leaders watched and

presided over the demise of the Beijing party leadership” since the criteria of

loyalty promoted by Lin Biao “could be applied to nearly anyone” by those

“wielding the power of interpretation” (p.

126). Why didn’t they resist this shift? Leese gestures vaguely towards

Mao’s entrenched “legitimacy” as an explanation of the CCP leadership’s

passivity in the face of what was, after all, a concerted attack on their

position, but I don’t think this rickety

Weberian catch-all term helps us very much to understand what happened

here. My sense is that under the conditions of pervasive distrust at the top of

the CCP, contradicting Lin carried higher risks individually (though greater lowered collective risks) than supporting him

or staying silent (which nevertheless increased collective risks); but this was

not so much because Mao was especially legitimate among the top leadership (whatever

that means) but because the party was too

publicly committed to him for objectors to feel confident that they could count

on the support of others if they went out of their way to argue against the

cult. (By the same token, they could be pretty certain that others would use

their words against them).

Interestingly, though Lin knew how to signal his

unconditional loyalty (in costly, even humiliating ways sometimes) he seems to

have had no special love for Mao himself. On the contrary, he seems not to have

liked Mao much, and to have promoted the cult in part as a way of protecting himself from the treacherous

shoals of politics at the apex of the CCP; he had seen (in Peng Dehuai’s case)

how even the merest hint of criticism could be turned by Mao (and others)

against the critic, with severe repercussions, and was determined to avoid a

similar fate. Leese quotes a 1949 private note of Lin’s on Mao’s political

tactics: “First he will fabricate “your” opinion for you; then he will change

your opinion, negate it, and re-fabricate it – Old Mao’s favourite trick. From

now on I should be wary of it” (p.

90). By 1959 Lin was adept at anticipating Mao’s position and changing his

opinion as soon as he sensed that the old opinion was no longer operative.

Lin used the cult not only to protect himself from the

vicious “court politics” of the CCP, but also to discipline the army and tamp

down dissatisfaction among the soldiers. The main tool he used to accomplish

this objective was similar to the original forms of “group study” that had been

used at the very beginnings of the cult, except more narrowly focused on Mao’s

writings and more ritualized. The “lively study and application of Mao Zedong

thought” was in practice reduced to learning to recite and use quotations from

Mao’s works as persuasive tools. But the particulars are fascinating; what

Leese describes is in effect the conscious construction of what Randall Collins

calls an “interaction

ritual” (really, go read

Collins – it’s enormously interesting stuff!) that shifted the “emotional

energy” of the troops and the party and increased their cohesion (Leese speaks

of “exegetical bonding,” which is quite a nice description too).

Contacts between the troops and their families were

monitored, but they were not necessarily directly censored. Instead, reports of

distress in the countryside were turned into “teaching moments” that extolled

the necessity of staying the course and blamed unfavourable weather or the

deviations of local officials from the correct line. Elaborate performances

making use of all kinds of media – big character posters, theatre, films,

poetry, etc. – recalled the “bitterness” of the past (before the communist

triumph) and extolled the “sweeteness” of the present (though, as one official

noted, “most comparisons of the present sweetness referred back to the period

of the land reform, whereas remarks about the Great Leap Forward were “inclined

to be abstract and without substance”,” p.

102), while presenting examples of communist martyrs for emulation. The

focus was on generating emotion by “remembering hardships” and then channelling

that emotion against the enemies of the communist project to achieve bonding.

The combination of peer pressure, genuine emotional experiences, and threats of

discipline for recalcitrance was clearly powerful, yet the party was aware of

the dangers of people merely “acting as if” they believed. Indeed, advice from

high up indicated that “cadres were not to insist on formalities such as the

weeping of participants as demonstration of their sincerity” (p.

100). But the very fact that such advice had to be given at all probably

shows that lower-level cadres did

insist on such performances just to be safe.

There were also campaigns to emulate “soldiers of Mao Zedong

thought,” which essentially meant soldiers who displayed the sorts of

self-sacrificing qualities that the party thought desirable. Here the cult

served, it seems to me, as a means by which certain kinds of status competition

were encouraged (the heroes of Mao Zedong thought, like Stakhanovite workers in

the Soviet Union, received media attention and other rewards), and hence

provided a positive incentive to adopt the “correct” sort of identity and

behaviour, complementing the negative incentives provided by peer pressure in

group study sessions or other collective interaction rituals. And as elsewhere,

status competition that is made to depend on the credibility of loyalty signals

appears to lead to inflationary pressures on flattery.

From the army, the more intense forms of the cult spread to

the broader population over time, accelerating as the Cultural Revolution

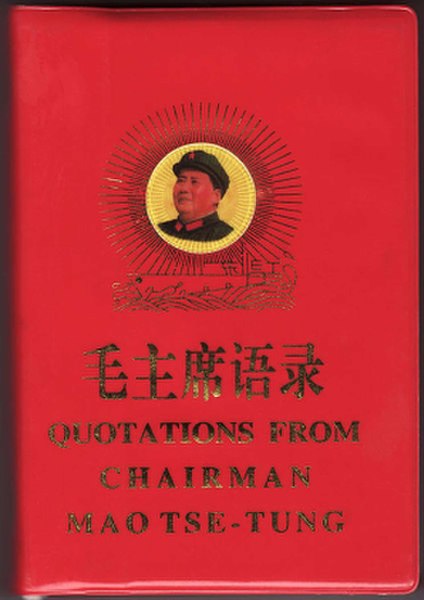

started. Leese tells the story of the creation of the “Little Red

Book,” for example, which was printed more than a billion times between

1966 and 1969:

|

| Image from wikimedia commons |

The Little Red Book was at first confined to the army, but

demand for it outside its confines was soon enormous. For one thing, political

study campaigns in the countryside (which increased in the 1960s) required a

focal text to mobilize people properly, and the Quotations provided one. But, as Leese astutely observes, the main

thing that the Quotations offered was

the “possibility of empowerment for non-party members” (p.

121). Though Leese does not put it this way, the book seemed to provide

access to the “code” that enabled people to act more or less safely within the

highly unpredictable environment of the early cultural revolution; and the

party enabled this demand by basically diverting the resources of the “entire

publishing sector” to printing Mao’s writings, “at the expense of every other

print item, including schoolbooks” (p.

122). Pace Leese, I think it is a

bit misleading to speak of the work’s “popularity”; the work was popular, if

that’s the word, because it was becoming essential for everyone to show some familiarity

with (read: be able to recite quotations from) Mao’s writings. Indeed, as Leese

documents later in the book, during the early cultural revolution Red Guards

would set up “temporary inspection offices” on the streets and harass

pedestrians about their knowledge of Mao’s works, like the “vice police” in

some countries today; this sort of atmosphere helped the cult to grow.

Other rituals were of course important to the spread of the more

intense forms of the cult outside the army. The eight “mass receptions” of the

Red Guards in 1966 were the most spectacular of these, though in some ways the

least interesting (to me). Though the Red Guards became a sort of vanguard in

the spread of the cult throughout Chinese society during the cultural

revolution, the actual number of people who participated in these receptions

would have been quite small relative to China’s total population, most of them impressionable

young students who took the advantage of free train travel to get involved in

something bigger than themselves. Under the circumstances, it is unsurprising

that many of them reported ecstatic experiences on seeing Mao (who didn’t make

any big speeches or direct them in any particular way), which in turn cemented

their identities as Red Guards; this sort of “interaction ritual” seems likely

to produce this sort of outcome fairly reliably, independently of any characteristics

of the supposedly “charismatic” figure (consider what happens at your typical

K-pop or J-pop concert). The more interesting point for me was about the role

that free train travel and accommodation played in encouraging the cult in

1966; for some people, at least, participation in the “exchange of experiences”

must have been a great opportunity to see China and engage in rebellious

activity with relatively low risk. (As Leese remarks, “many students displayed much

more revolutionary fervor in distant places than at home, where they had to

consider other interests involved,” p.

139).

As the cult spread and the chaos of the Cultural Revolution

deepened, however, the party lost control over its symbols. Leese refers to

this as the period of “cult anarchy;” I would compare it to the point at which

monetary authorities lose control of the money supply, leading to runaway

hyperinflation. Different factions of Red Guards started using Mao’s image and

words in incompatible ways, and new cult rituals emerged from the grass roots,

sometimes from the enthusiasm of the genuinely committed, sometimes seemingly

as protective talismans against the uncertainty and strife of the period. Everybody

appealed to Mao to signal their revolutionary credentials, but there was no

longer anyone capable of settling disputes over the credibility of these

signals. Mao himself wasn’t much help; whenever he spoke at all, his messages

were often cryptic and didn’t really settle any important disputes. The cult

was now a “Red Queen”

race of wasteful signalling, rather than a carefully calibrated tool of mobilization

or discipline, driven by a complex combination of genuine desires to signal

loyalty and identity and fears for one’s security. (Leese notes that failure to

conform to the arbitrary protocols of the cult put people at risk of being

sentenced as an “active counterrevolutionary” and documents many cases in which

minimal symbolic transgressions resulted in incarceration or even death).

By 1967, for example, statues of Mao first started to be

built, something that CCP leaders, and Mao himself, had discouraged in the

past, and still officially frowned upon. The statues were typically built by

local factions without approval from the central party, and they were all 7.1

meters high and placed on a pedestal that was 5.16 meters high, for a total

height of 12.26 meters. (26 December = Mao’s birthday, 1 July = the Party’s

founding date, 16 May = the beginning of the cultural revolution. People

arrived at this precise convention for the statues without any centralized

direction, merely through a signalling process). Later “Long Live the Victory

of Mao Zedong Though Halls” were built on a grand scale, again without approval

from the central party. Billions of Chairman Mao badges were produced by

individual work units competing with each other, which were themselves subject

to size inflation (“[a]s the larger size of the badges came to be associated

with greater loyalty to the CCP Chairman, … badges with a diameter of 30

centimetres and greater came to be produced,” p. 216); Zhou Enlai would grumble in

1969 about the enormous waste of resources this represented. Costly signalling

demands kept escalating; some people took to pinning the badges directly on

their skin, for example, and farmers sent “loyalty pigs” to Mao as gifts (pigs

with a shaved “loyalty” character).

New rituals and performances emerged too: Leese discusses

the “quotation gymnastics,” a series of gymnastics exercises with a storyline

based on Mao’s thought and involving praise of the “reddest red sun in our

hearts,” and more bizarrely perhaps, “loyalty

dances,” (picture

at the link) which, like the quotation gymnastics, was “a grassroots

invention” designed to physically signal loyalty, and which spread “even to

regions where public dancing was not part of the common culture and thus led to

considerable public embarrassment” (p. 205). People wrote the character for

“loyalty” everywhere and developed new conventions for answering the phone that

started by wishing Mao eternal life. One of the most bizarre and interesting

stories in the book concerns “Mao’s mangos:” the story of how some mangos that

Mao gave to a “Propaganda Team” became relics beyond the control of the Central

Party. Let me quote from Adam Yuet

Chau’s article on the mangos as relics (Past and Present (2010) 206 (suppl 5): 256-275), which has a much better summary

than anything I can manage:

On 5 August 1968, Mao received

the Pakistani foreign minister Mian Arshad Hussain, who brought with him a

basket of golden mangoes as gifts for the Chairman. Instead of eating the

mangoes, Mao decided to give them to the Capital Worker and Peasant Mao Zedong

Thought Propaganda Team … that had earlier been sent to the Qinghua University

in Beijing to rein in the rival Red Guard gangs. Two days later, on 7 August,

the People’s Daily, the official news organ of the Communist

Party-state, carried a report on the mango gift that included the following

extra-long headline in extra-large font: ‘The greatest concern, the greatest

trust, the greatest support, the greatest encouragement; our great leader

Chairman Mao’s heart is always linked with the hearts of the masses; Chairman

Mao gave the precious gifts given by a foreign friend to the Capital Worker and

Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team’.

Yuet Chau then quotes an eyewitness:

Mao gave the mangoes to Wang

Dongxing, who divided them up, distributing one mango each to a number of

leading factories in Beijing, including Beijing Textile Factory, where I was

then living. The workers at the factory held a huge ceremony, rich in the

recitation of Mao’s words, to welcome the arrival of the mango, then sealed the

fruit in wax, hoping to preserve it for posterity. The mangoes became sacred

relics, objects of veneration. The wax-covered fruit was placed on an altar in

the factory auditorium, and workers lined up to file past it, solemnly bowing

as they walked by. No one had thought to sterilize the mango before sealing it,

however, and after a few days on display, it began to show signs of rot. The

revolutionary committee of the factory retrieved the rotting mango, peeled it,

then boiled the flesh in a huge pot of water. Mao again was greatly venerated,

and the gift of the mango was lauded as evidence of the Chairman's deep concern

for the workers. Then everyone in the factory filed by and each worker drank a

spoonful of the water in which the sacred mango had been boiled. After that,

the revolutionary committee ordered a wax model of the original mango. The

replica was duly made and placed on the altar to replace the real fruit, and

workers continued to file by, their veneration for the sacred object in no

apparent way diminished.

Here’s a picture of one of the

mangos, from Stefan R. Landsberger’s

fantastic collection of Chinese Cultural Revolution posters; the poster is

based on a photograph taken very shortly after the gift of the mangos:

|

| Figure 5: "The great leader Chairman Mao's treasured gift to the Workers' Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Teams of the capital - a mango" (1969). From Stefan R. Landsberger's collection. |

“Mango fever” then spread

throughout the country:

In order to share the honour with

workers and the revolutionary masses elsewhere, more replicas of the mangoes

were made and sent around the country. All over the country welcoming parties

were organized to receive the mangoes, and many work units enshrined the mango

replicas for the masses to view in order to partake in the Chairman’s gift. Mao

badges with the platter of mangoes and posters with revolutionary messages

illustrated with the mangoes began to appear; a cigarette factory in the city

of Xinzheng in Henan Province began producing a line of mango-brand cigarettes

(still in production today); a film was made on class struggle using the Mao

mango gift as a key symbol in the story line. In the months following Mao’s

giving of the mangoes a mango fever descended upon China.

It’s worth noting that mangos were very rare in China at the

time; few people would have seen one, so they were more likely objects of

curiosity than one might have expected. A detail from another 1969

poster gives some of the flavour of the mango processions (though actual

pictures of these events, one of which is included in Leese’s book, show the

mangos inside covered reliquaries):

|

| Figure 6: Detail from poster "Forging ahead courageously while following the great leader Chairman Mao!" (1969). From Stefan R. Landsberger's collection. |

As Leese notes, most of these inventions (the mango rituals

included) were not authorized by the CCP Centre, and many of the supposed

leaders of the cultural revolution (e.g., Kang Sheng, Jiang Qing, and occasionally

even Mao himself) tried to curb their practice, or at best only grudgingly

authorized them after the fact. From their perspective, these “grassroots”

practices and rituals were objectionable because they could not be controlled

directly by them.

But it would be a mistake to think that because these

practices were not directed from the top, that they were therefore genuine

expressions of love for the Chairman. Motivations were of course various, and

one does not want to preclude positive affect by definition– those who adopted

the identity of “Red Guards” probably thought of themselves as sincerely in

love with Mao, for one thing – but whatever people’s motivations may have been

they were clearly dominated by the

need to signal loyalty against a background of others who were also furiously trying to signal loyalty

for their own manifold reasons. The clearest evidence of signalling behaviour is

in fact the uniformity of the language

used to flatter Mao (“down to the level of single phrases” over thousands of

texts p. 184: "boundless hot love," "the reddest red sun in our hearts," etc.); the language of flattery was a code to be mastered, not a way of expressing deeply held emotions,

as Leese rightly sees.

This is not to say that flattery was never sincere or

reflective of great love for Mao; but its escalation came from the Red Queen

race aspect of the situation, not from some deep well of emotion or from awareness

of Mao’s charismatic qualities. And this Red Queen race was reinforced by the

presence of a small core activist group – the Red Guards at first - that was

quite capable of inflicting punishment, directly or indirectly, on those who

did not conform. At any rate, as Randall

Collins says: “Sincerity is not an important question in politics, because

sincere belief is a social product: successful IRs [interaction rituals] make

people into sincere believers.” But lose the rituals, and you easily lose the group

identities and emotional energy that drive action; sincere belief is rarely an independent driver of action.

It is also unsurprising that such “grassroots” loyalty

signalling would tend to draw on various traditional scripts for demonstrating

reverence or support, including scripts connected with the veneration of relics

in Buddhism (as in the case of the mangos) or other forms of religious worship;

the signal has to be recognizable to arbitrary others, and only religious scripts

have sufficient universality for this purpose. Similarly, some of the

manifestations of the cult (painting loyalty characters all over one’s house)

can only be understood in terms of what I would call “magical thinking” – the use

of words and objects to ward off evil pre-emptively. (But, unlike other forms of

magical thinking, this stuff worked!). There is, in short, little need to appeal

to tradition, “feudal” remnants, collective backwardness, or superstition to

explain any aspect of the cult, contrary to the standard accounts of the cult offered by

communist party theoreticians (and many people today).

This post is already long enough, but it is worth noting that

the party seems to have tried to regain control over cult symbols by ratcheting

the ritual level up – making the cult

protocols more arbitrary – to foster unity in the factionalized atmosphere of

the Cultural Revolution. The degree of ritualization was astonishing; Mao

quotations came to be used in the most banal exchanges (answering the phone,

buying produce, etc.); work units were required to “ask for instructions in the

morning” before a portrait of Mao; etc. But the disciplinary function was

clear: “[d]eviations from the prescribed routines were regarded as disloyal

behaviour and thus potentially engendered drastic consequences” (p. 199). Once

direct control over the symbols of loyalty was re-established, the party could

move to gradually control flattery inflation and even engage in some controlled

disinflation.

Though Leese does not put it this way, his overall story

suggests that the Mao cult went through about six different stages, each of

which can be distinguished by its own distinctive “inflationary” drivers on

flattery of Mao. The first stage can be characterized as one of “controlled

inflation,” lasting from the initial building up of the cult in the late 1930s

and early 1940s to Stalin’s death, more or less. At this time, the cult was

fostered by the entire party leadership and served primarily a mobilizing function, though the party

was careful to prevent excessive praise of Mao; we might say that the initial

cult building project shifted the base level

of flattery upwards, but did not yet produce powerful inflationary pressures on

the growth of flattery. The second

stage, lasting from Stalin’s death to the failure of the “Hundred Flowers”

campaign, more or less, can be characterized as one of slight flattery

“deflation.” At this time, a number of events, including Khrushchev’s Secret Speech,

prompted a certain amount of liberalization directed from above that led to a

slight lowering in the level of flattery and a relaxation of inflationary

pressures. With the failure of the “Hundred Flowers” campaign, the cult enters

a stage of “sustained inflation,” and control over the cult shifts to Mao and

his close associates, who promote it primarily for disciplinary purposes. This stage lasts until the beginning of the

Cultural Revolution, when they lost full control over the symbols of the cult.

At this point (stage four) we have “runaway inflation”, driven by the need to

signal loyalty in factional struggles and avoid punishment. By 1971, however,

the party had regained some control over cult symbols, Lin Biao had fallen from

grace, and the party engaged in some flattery deflation, helped somewhat by the

death of Mao in 1976. (Interestingly, there was not a great deal of spontaneous

public grief at the time; as Leese notes, most people were probably rather

cynically disenchanted with Mao by then. The old rituals of the cult had lost

their emotional power). Finally, one may add the resurgence of something like a

posthumous Mao cult after 1989. Here cult practices are driven by many

motivations – “disillusionment, nostalgia, renewed national pride, the

incorporation of religious traditions, and commercial interests” (p. 262) lifting

the background level of flattery from its nadir in the late 1970s and early

1980s, but incapable of sustaining runaway flattery inflation in the absence of

encouragement from the CCP Center, which can’t live with Mao, and can’t live

without him.

A few general lessons may perhaps be drawn from this story.

First, cults of personality basically never emerge from the spontaneous

expression of emotion by a population, despite what dictators may have you

believe. They are primarily tools of political control within networks of patronage

relationships, as Leese rightly sees (hence, in practice, much more likely to emerge in highly authoritarian contexts). I have compared them here to the tools of

monetary policy in the economic realm, insofar as they affect the average level

of effort invested in signalling loyalty to a ruling group or person (the “flattery

level”); but, as with monetary policy, cults can miscarry – in which case uncontrolled

flattery inflation may result. Second, their effects are not produced by mere propaganda; interaction rituals are required

to produce genuine emotional energy within specific groups, increase cohesion, etc. But the cult does not depend on the genuineness of anybody’s

sentiments to work; it depends on the possibility of producing certain kinds of emotional pressures through group

rituals. (As an aside, we lack a good “high pressure” political science and psychology;

too much of our political science and psychology assume “low pressure”

environments. But cults are high pressure phenomena, and attempting to

understand them by means of the stories and concepts we use in low pressure

environments is apt to lead us astray). Finally, the rickety Weberian apparatus

of “legitimacy” and “charisma” is basically irrelevant to the explanation of cults.

Leese’s book is mercifully free of those terms, except for the occasional sentence

claiming that so and so’s actions “legitimized” this or that; but most of these

can be safely ignored (all the sentence can possibly mean is “increased support”).

All in all, this is an excellent book – highly recommended

if you are interested in the topic, though it does assume a great deal of

background knowledge of modern Chinese history.